Akhenaten’s Purgatory: Dissecting the Legend of the Mad Pharaoh’s Cursed Soul

Called “the first individual in history” by historian James Henry Breasted, the Pharaoh Akhenaten is one of the most fascinating and bizarre rulers of Ancient Egypt. Born as Amenhotep to Pharaoh Amenhotep III and his wife Tiye in c. 1363-1361 BCE, Akhenaten reigned as Pharaoh during Egypt’s 18th Dynasty alongside his wife Nefertiti. He was the father of around eight children, possibly including the famous child-pharaoh Tutankhamun (aka King Tut). The first few years of Akhenaten’s reign followed previously established traditions, including the acceptance of polytheistic religion and conforming to the long standing Egyptian artistic style. But for the first time in Egyptian history, traditions were about to be thrown out the window and a religious revolution was beginning to brew.

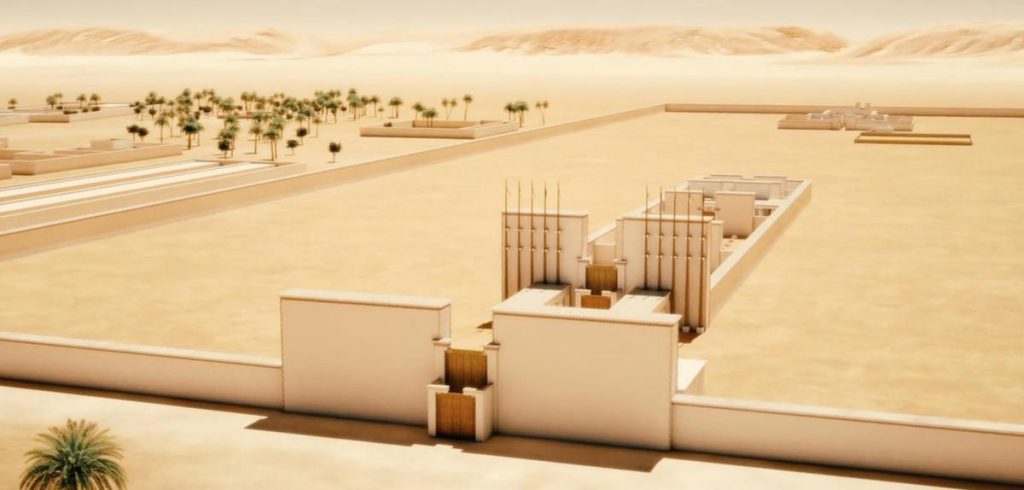

Following his name change from Amenhotep to Akhenaten, the pharaoh began making drastic and unprecedented changes, such as moving the capital from Thebes to the Pharaoh’s newly constructed city Akhetaten (known today as Amarna) on the east bank of the Nile. But the most radical and notable change was his creation of what some historians believed to be the world’s first known monolithic religion, casting aside “one of the largest and most complex pantheons of gods in any civilization in the ancient world” in favour of the sole worship of the Aten through a new religious system called Atenism.

The Aten was a sun god depicted as the disc and rays of the sun. As a sign of devotion to his god, Akhenaten removed all references to other ancient Egyptian deities including Amon, king of the gods and the patron god of the pharaohs. Even the writing of the word ‘gods’ as plural was removed in some cases. The Pharaoh not only aligned himself with the Aten, but saw himself as the deity’s earthly manifestation. In Akhenaten’s lengthy poem Great Hymn to the Aten he praised the Aten as the giver of life and the reason for mankind’s existence:

[Those on] Earth come from your hand as you made them.

From Great Hymn to the Aten c. mid 14th-century, translated by Miriam Lichtheim (source)

When you have dawned they live.

When you set they die;

You yourself are lifetime, one lives by you.

All eyes are on [your] beauty until you set.

All labor ceases when you rest in the west;

When you rise you stir [everyone] for the King,

Every leg is on the move since you founded the Earth.

Alongside the emergence of the cult of Aten came the construction of magnificent open-air temples and decadent artworks showcasing the new and revolutionary style that came to be known as ‘Amarna art’, which was defined by androgynous figures with large heads, narrow eyes, long necks, slim bodies, and large thighs and bellies. Construction of the new capital Akhetaten was a massive and fast paced building project requiring an incredible amount of labour to construct not only the temples and thousands of houses, but also palaces, tombs, roads, and cemeteries. Three years after construction began Akhetaten was completed and the biggest cultural revolution to ever take place in the history of Ancient Egypt had commenced.

But less than two decades after the completion of Akhetaten, the new city was completely abandoned. No one really knows how Akhenaten died or where his body is (possibly in tomb KV55 in the Valley of the Kings), but when Tutankhamun became pharaoh changes were implemented to revert pretty much everything Akhenaten had done and everyone tried to pretend none of it ever happened. Priests who had been stripped of their roles had their titles restored, new statues were commissioned for the deities Amon and Ptah, the capital was moved back to Thebes, worship of the Aten was renounced and polytheistic religion was restored. Tutankhamun, who’s name was originally Tutankhaten, had the ‘aten’ removed from his name and replaced with ‘amun’ in acknowledgment of the rightful king of the gods, and the young king began restoring temples throughout Egypt that had been destroyed or pillaged by Akhenaten. Not a trace of Akhenaten would remain visible and the rebel Pharaoh faded into obscurity.

Dissecting the Legend of the Wandering Pharaoh

So what exactly happens to the soul (or ka) of an Egyptian Pharaoh who denounced the gods and made efforts to destroy their temples?

According to legend, the angered priests of Egypt put a curse on Akhenaten upon his death to wander the great expanse of The White Desert of Farafra for all of eternity as punishment for abolishing their jobs, their gods, and the destruction of their temples. Barred from the afterlife, some travellers claim to see the ghost of Akhenaten walking aimlessly through the desert. Those who enter the The White Desert are warned not to approach or talk with the ghostly Pharaoh or they will be cursed to join him in his eternal limbo.

A short and snappy legend, but where did it come from?

In his book The Life and Times of Akhnaton, Pharaoh of Egypt (first published in 1910), Egyptologist Arthur Weigall (dramatically but impactfully) describes how the ‘excommunication of a soul’ would have been understood by Ancient Egyptians and describes Akhenaten’s cursed eternal fate when his name was erased from history:

It is not easy now to realise the fully meaning to the Egyptian of the excommunication of a soul : cut off from the comforts of human prayers ; hungry, forlorn, and wholly desolate ; forced to last to whine upon the outskirts of villages, to snivel upon the dung-heaps, to rake with shadowy fingers amidst the refuse of mean streets for fragments of decayed food with which to allay the pangs of hunger caused by the absence of funeral-offerings. To such a pitiful fate the priests of Amon consigned “the first individual in history” ; and as an outcast amongst outcasts, a whimpering shadow in a place of shadows, men of Thebes bade us leave the great idealist, doomed, as they supposed, to the horrors of a life which will not end, to the misery of a death that brings no oblivion.

The Life and Times of Akhnaton, Pharaoh of Egypt (New and Revised Edition, 1922) by Arthur Weigall, page 245.

While I couldn’t find a direct source for the legend, Weigall’s description of Akhenaten’s damnation could certainly inspire stories surrounding the sighting of the Pharaoh’s wandering ghost. But a spooky spin on the infamous Pharaoh’s fate was already playing on Weigall’s mind when, a year before The Life and Times of Akhnaton was published, the Egyptologist, his wife, and two friends created and rehearsed an infamous ‘cursed play’:

In 1909, Weigall, his wife Hortense, the painter Joseph Lindon Smith and writer F. F. Ogilvie decided to stage a play about the heretic pharaoh Akhenaten in a natural amphitheatre in the Valley of the Queens. Weigall composed the script, and poured his energy into framing a ghost story for the spooky invite, which told a tale of Akhenaten’s spirit returning to the valley every year on the same night for three thousand years. At their first rehearsal the cast were struck down with various illnesses (Mrs Smith with ophthalmia and delirium) and the play was abandoned. The story, thrilling with the possibility of malign supernatural intervention, had been widely circulated, reaching as far as the London press. Weigall himself wrote up the events for Pall Mall Magazine , where he honed his suspension of disbelief. Despite ‘the most absurd nonsense talked in Egypt’, he said, ‘at the same time I have there become acquainted with certain facts which are far removed from simple explanation .’ He also delighted in spooking tourists in Luxor, writing to his wife that ‘the great stunt is to take people to the cave and tell them the story of the play – it never fails to go down.’

The Mummy’s Curse: The True History of a Dark Fantasy by Roger Luckhurst (2012), page 12.

The Pall Mall Magazine article mentioned in the above excerpt from Roger Luckhurst’s book The Mummy’s Curse refers to ‘The Ghosts of the Valley of the Tombs of the Queens’, which Weigall had published in the Pall Mall Gazette in June 1912. While I can find academic papers directly referencing this article, I haven’t been able to find a scan of it anywhere online, including The British Newspaper Archive. [As a side note, if anyone has access to a scan of this article I would love to give it a read.]

So while it isn’t a direct source, our cursed legend of the wandering soul of Akhenaten seems to stem from Arthur Weigall’s ‘cursed play’. But one of the most confusing aspects of the legend is the inclusion of The White Desert in Farafra, which is located absolutely no where near the Valley of Queens (according to Google Maps you’re looking at a multi-day trek by foot). Why is Akhenaten’s ghost haunting the White Desert when it has more than enough reason to haunt locations such as present day Amarna, the Valley of Queens, or the Valley of Kings where he’s thought to be buried? Who decided this legend would take place in such a seemingly random location? Has word of mouth muddled it over the years? Or is this based on an oral tradition that isn’t readily available to read online? I would have personally preferred a version of the legend where Akhenaten’s spirit wanders the ruins of his open-air temples in Akhetaten/Amarna, praying to the Aten to free him from his eternal limbo. But that’s just me.

Wherever the present day version of this legend came from, Akhenaten is without a doubt one of the most fascinating Egyptian pharaohs. Efforts to remove him from the history books was done in vein as he is now one of the most popular Egyptian pharaohs alongside Tutankhamun, Ramses II, Khufu, and Cleopatra. But the endless mysteries surrounding his life and death continue to puzzle and enchant archaeologists, unanswered questions perhaps more haunting than the White Desert that house’s the Pharaoh’s wandering soul.

Sources and Additional Reading

American Research Centre in Egypt – Akhenaten: The Mysteries of Religious Revolution

Amarna Project – Model of the City

BBC Travel – Bahariya and Farafra: Egypt’s bizarre, desert landscape (2020)

Britannica – 11 Egyptian Gods and Goddesses / Aton

Google Arts & Culture – Ghost World: 6 Most Haunted Sites

Luckhurst, Roger. The Mummy’s Curse: The True History of a Dark Fantasy. OUP Oxford (2012)

The Travel – 10 Allegedly Haunted Places You Can Visit in Egypt (2022)

University of Cambridge, Department of Archaeology – Life in Ancient Egypt: Amarna, Resources for Schools

Weigall, Arthur. The Life and Times of Akhnaton, Pharaoh of Egypt. New and Revised Edition. Thornton Butterworth Limited, London (1922)

Wikipedia – Akhenaten / Amarna / Aten / Farafra, Egypt / White Desert National Park