The Bizarre Exploits of Helen Duncan: Ectoplasm Producing Medium and Britain’s ‘Last Witch’

Helen Duncan, ‘the last witch’ of Britain, was born in the small town of Callander, Scotland in 1897 to Archibald McFarlane and Isabella Rattray. As a child, Helen (born Victoria Helen) was said to cause distress at school by tormenting her classmates with frightening prophesies. And from a young age Helen believed she was clairvoyant and could see the spirits of the dead. Her behaviour, along with her stormy temper, earned her the nickname ‘Hellish Nell’.

In 1916, eighteen-year-old Helen married cabinet maker and invalided WWI veteran Henry Duncan. When first introduced, Henry greeted Helen with “So we meet at last,” as the couple claimed to have visions of one another before they met. Helen and Henry had six children (Bella, Nan, Lillian, Henry, Peter, Gena) while Helen worked part-time at a bleach factory to help feed their large family. Henry was supportive of his wife’s paranormal abilities and encouraged her to develop her unique gift, but Helen was reluctant due to the negative reactions she had received as a child. But with an increase of families losing loved ones during the war, there were plenty of people who sought comfort in their grief from mediums. So in 1926 Helen followed her husband’s advice and began hosting séances.

Helen’s Séances and the Curious Art of Ectoplasm

Helen’s séances had a particular setup. To prove her authenticity, Helen had a female attendee examine her naked before donning a black gown and entering the séance space. During many of her séances, Helen sat in a curtained cabinet (some say this was designed by her husband), but it isn’t clear if this prop was included each time she performed.

During her séances, Helen was joined by her spirit guides Albert Stewart, a pattern-maker from Dundee who emigrated and died in Australia, and a young girl named Peggy. Helen’s spirit guides would speak through the medium while she was in a trance with their own voices and personalities (Albert was said to speak with a drawl), to pass messages from beyond the veil. Between the two, Albert was the dominate guide and made appearances more frequently than Peggy. But at least one of Helen’s two spirit guides appear in written accounts of her many séances, making Albert and Peggy leading characters of the spectacle.

So what made Helen’s séances so special? While some mediums simply channelled spirits of the dead, Helen boasted the impressive feat of physically manifesting her spirit guides in front of shocked attendees. If you think this sounds too good to be true, you’re absolutely correct.

Anyone interested in Victorian and early twentieth-century spiritualism will have stumbled upon black and white photographs of mediums ‘manifesting’ the physical form of a ‘spirit’ from a bodily orifice (mouths, ears, noses, and eyes). This physical form was referred to as ectoplasm and, to the modern-day eye, looks incredibly corny and obviously fake. However, during Duncan’s lifetime, mediums were taken so seriously that some believers would pay thousands of pounds for a séance and even go as far as giving away their houses and remaking their wills. And to many people, the figures manifested via ectoplasm were considered the real deal (or at least they convinced themselves they were).

By the end of the 1920s, Helen was considered one of the most famous mediums in Britain. Henry’s encouragement of Helen’s gift paid off (literally) and he travelled with his wife around the country to assist with her séances. While Helen’s performances garnered positive attention from supporters, there were plenty who looked past the magic and saw what was actually going on.

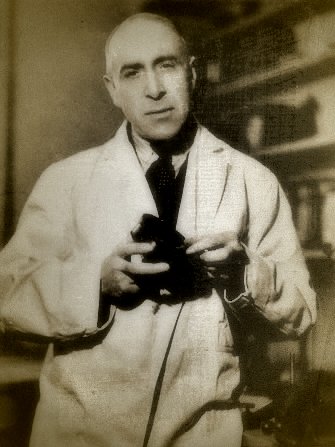

Harry Price and the ‘Cheese-Cloth Mania’

Helen came to the attention of paranormal investigator Harry Price in a 1929 ‘spiritualist press’ article, which left the infamous sceptic with more questions than answers. After receiving a sample of her ‘teleplasm’ (another word for ectoplasm) he began a thorough investigation into the country’s favourite medium. “I read of séances, held almost in full light, at which phantoms materialised out of space, danced, sang, joked, walked about the room, and hobnobbed with the sitters generally,” Price wrote in his Leaves from a Psychist’s Case-Book, “as I do not believe one-tenth of what I read in the spiritualist press, I was not particularly thrilled.” After confirming the teleplasm sample he’d received was an egg white mixed with other chemicals, Price created his own teleplasm sample and published the recipe in his book:

White of a new-laid egg.

Ferric chloride.

Phosphoric acid and urine mixed with gelatine.

Hot margaric acid from olive oil.So now the reader knows what ghosts are made of!

Leaves from a Psychist’s Case-Book by Harry Price (1933), pg. 201.

After Price began his investigation, Helen visited London at the invitation of the city’s spiritual societies and Price watched in disbelief as spiritualists flocked to witness what he considered an obvious case of fraud. A séance was then held in the same building as Price’s National Laboratory of Psychical Research, but he wasn’t invited to join. The séance was a success, the spiritualists very impressed, and Price noted grimly that “the cheese-cloth mania had started“. During the following six months, Helen conducted regular séances with the spiritualists where a ‘substantial fee’ was charged to witness the medium in action. Price submitted an application to sit in on one of the séances but “the spiritualists refused point blank to allow me even to set foot in the séance room! What were they afraid of?”

However in April of 1931, Henry approached Price and offered to have his wife perform a séance at the National Laboratory of Psychical Research, much to Price’s surprise.

The following month on 4 May, Price conducted “the first scientific test ever held with the woman” with a number of ‘distinguished people’ present, including psychologist Dr William McDougall, F.R.S. The clothing Helen brought with her was carefully examined, but a medical examination wasn’t conducted since Price and his colleagues wanted to see the medium in action before putting controls in place. He describes the opening of the séance in his book:

The medium having donned her special garments, she was led into the séance-room by Professor McDougall and myself, and placed in the curtained recess known as the cabinet…. In a few seconds the medium was in a trance, and within a minute the cabinet curtains parted and we beheld the medium covered from head to foot with cheese-cloth! There appeared to be yards of it. Some of it was trailing on the floor; one end was poked up her nostril; a piece of issuing from her mouth. It moved, it withered, it waggled, it squirmed on the floor, it spread itself out like an apron. Then the medium closed the curtains and the spectacle was hidden from view. All these transformations and permutations took place in a red light bright enough to read small print by. Every person and object in the séance-room was plainly visible.

Leaves from a Psychist’s Case-Book by Harry Price (1933), pg. 202.

Behind the curtains the voices of Helen’s spirit guides Albert and Peggy could be heard. And when the curtains opened back up Helen’s body was draped with a sort of shawl, or what Price described as “more cheese-cloth“. Price examined the ectoplasm with his hands and mentally confirmed that it was almost certainly cheesecloth, that it was damp, and that it smelled like ‘ripe gorgonzola’. Helen was then willingly bound to her chair with surgical tape to confirm if any tricks were being played (Albert agreed that this was suitable). However, Helen was no longer able to perform because, as Albert explained, Helen’s circulation had been cut off. The séance concluded before 10PM and Price had some strong feelings about what he had witnessed:

… and I must say that I was deeply impressed: I was impressed with the brazen effrontery that prompted the Duncans to come to my Laboratory in an attempt to “put over” their stuff on our experts; I was impressed with the amazing credulity of the spiritualists who had sat with the Duncans for six solid months, and with the fact that they had advertised her “phenomena” as genuine.

Leaves from a Psychist’s Case-Book by Harry Price (1933), pg. 203.

The only real mystery was where Helen was keeping the cheesecloth. Since a medical examination was forgone, it was suspected that the cheese-cloth was being kept inside her body, which was a common trick of mediums.

Additional séances with Helen were conducted with Price’s team at his laboratory and Price requested to take photos of the ectoplasm as it appeared from Helen’s body, instead of hiding behind the curtain. Helen agreed.

The photographs confirmed Price’s suspicions once again: cheesecloth was definitely being used to form the spirits of Albert and Peggy. The photographs also showed a surgical glove had been used to give the illusion of a ‘spirit hand’ at the end of the ectoplasm, and the face of Peggy was simply a magazine cut-out. But the question of where Helen was keeping the cheesecloth continued to baffle Price and his colleagues. So a medical examination of ‘every orifice’ of Helen was conducted… but no ectoplasm was found. He concluded that the only location that hadn’t been checked was Helen’s stomach.

During the fourth séance on 28 May 1931 an x-ray machine was wheeled into the room and “at the sight of the apparatus the medium seemed scared, and promptly went off into another alleged trance“. After an outburst (which involved punching Henry in the face while he tried to talk his wife into having the x-ray), Helen ran from the building and into the streets ‘in alleged hysterics’. Due to gathering crowds the authorities were called to calm the chaos. Helen eventually returned to the Laboratory and offered to have the x-ray done, but Price said the controls had been broken and doing an x-ray now was pointless. Price suspected that for the brief moment Helen was alone with her husband before returning to the Laboratory she had ‘passed the cheese-cloth’ to him. This was confirmed when Price asked Henry to turn out his pockets and he refused.

Surprisingly, Helen agreed to final séance on 4 June where Albert allowed a piece of his ectoplasm sample to be cut by a member of Price’s team. Another thorough medical examination was conducted, this time by hospital staff, but once again nothing was found. So when the white substance of Albert’s ectoplasm emerged from Helen’s mouth, a piece was cut off before the rest was swallowed back down Helen’s throat. Price and his team suspected it was a flattened tube of paper. The sample was passed on to Mr William Bacon, a chief analyst to the paper trade who declared it was “merely a cheap, thin paper, like a strip of a toiler roll, soaked in white of egg and folded into a flattened tube“.

Following Price’s meeting with Mr Bacon, Price and Henry agreed to one more séance with additional physical controls in place on 2 July. However, the Duncans left London for Scotland without warning on 23 June. Price’s final conclusion was that Helen was a regurgitator, which allowed her to swallow objects and bring them back up at will, creating the illusion that the spirit of Albert or Peggy was willingly emerging from her body. But despite Price’s critical findings, Helen’s popularity continued to grow:

The reader might well imagine that my damning report on the Duncans finished the “mediumship.” Not a bit of it! It acted as an excellent advertisement for the woman and her curious powers, and spiritualists on both sides of the Tweed began falling over themselves in order to obtain sittings with her. The cheese-cloth mania had a fresh lease on life.

Leaves from a Psychist’s Case-Book by Harry Price (1933), pg. 208.

After Helen and Henry left London, Price was contacted by a Miss Mary McGinlay in February of 1932 who had previously worked as Helen’s maid in London. Miss McGinlay said that Helen had her buy pieces of butter-muslin, which looked identical to the ectoplasm samples Price had photographed. She also said that Helen would give her the pieces of cloth after her séances for washing. Miss McGinlay told Price, “the muslin had a rotten smell. It put me in mind of the smell of urine… She would give it to me just as she had used it, and then it would be much stained and slimy.” She believed that the cloth had been swallowed and regurgitated by Helen during her séances. A crucial piece of information from Miss McGinlay was that on the night of the proposed x-ray when Helen ran into the street in hysterics, Henry had given Miss McGinlay a ‘roll of butter-muslin’ from his pocket and said Helen had given it to him after she had fled from the Laboratory. Miss McGinley’s testimony was satisfying confirmation for Price and backed up his suspicions of Helen and Henry’s deceitful game.

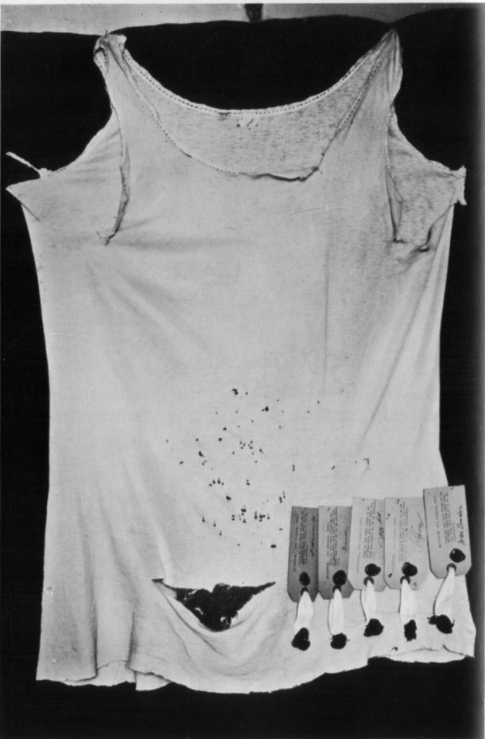

The following January, Miss Esson Maule was hosting a séance with Helen and “some well-known Edinburgh people” when the performance took a dramatic turn. Miss Maule grabbed onto the ectoplasm of ‘Peggy’ and a bizarre tug-of-war commenced between the medium and the host. Peggy was ripped in the process, with damage done to the ‘spirit’ visible in the photograph above. Amongst the chaos, the police were called and Helen was required to hand over ‘Peggy’, which attendees called “a woman’s stockinette undervest”. The garment, along with the signatures of the attendees, was sealed and taken away by police. On 3 May, Helen was tried for fraudulent mediumship, found guilty, and fined £10. But this wasn’t Helen’s last run in with authorities. The infamous medium’s next trip to court was for a much more outlandish offence.

Helen Under Surveillance

In 1941 during the Second World War, Helen had returned to England and lived in Portsmouth, home of the Royal Navy. During her time in Portsmouth, two suspicious events occurred at Helen’s séance’s putting her on the navy’s radar. In May, Brigadier Roy C. Firebrace was among the sitters at one of Helen’s séances when her spirit guide Albert informed the group that a British battleship had tragically sunk. Firebrace hadn’t heard of the sinking and, after enquiring with members of the Royal Navy, concluded that Helen’s prophecy was incorrect. However, the next day he learned that the HMS Hood had sunk during the Battle of Denmark Strait — the same day as Helen’s séance. But how would Helen have known information that had yet to be disclosed to the public?

The second suspicious incident occurred in November that year. During a séance, Helen was informed by Albert that the spirit of a dead sailor was present and that he had a message for a woman in attendance. Helen informed the woman that the dead sailor was her son and he wanted his mother to know he died at sea when his ship tragically sunk. The woman’s son was on the HMS Barham, which was torpedoed by German submarine U-331 resulting in a massive explosion (see video above). A total of 862 members of the crew lost their lives. However, at the time of the séance, the next of kin had yet to be notified by the War Office and the Board of Admiralty had kept the attack a secret from the public. This was to mislead the enemy as well as protect public morale, a common occurrence during the war. It didn’t take long for rumours of the HMS Barham’s sinking to spread around Portsmouth, ruffling the feathers of the navy who were desperate to keep the sinking confidential until the planned announcement to the public on 27 January 1942. The navy now had an unusual problem — a local medium was somehow privy to top secret information and was spreading it during her séances.

After the second incident, the authorities kept a close eye on Helen. And two years later on the night of 19th January 1944 her séance was raided by police when an undercover officer hid among the spectators and blew a whistle to alert the other officers waiting outside. The raid was apparently coordinated due to growing concern that Helen would reveal details of the approaching D-Day Normandy landings during one of her séances. However, the reason the whistle was blown during that particular séance isn’t known. At that moment of the raid, Duncan was in the process of dispelling ectoplasm, which the police failed to grab onto in the panic.

Helen and three sitters were arrested on charges of conspiracy and taken to the Portsmouth Magistrates’ Court where she was originally charged under Section 4 the Vagrancy Act (1824). Section 4 of the act, according to Scottish Charity The Pavement is “the ‘rogues and vagabonds’ category [that] enabled the authorities to apprehend on the street anyone they disliked“. This ranged from the homeless and minstrels to fortune-tellers and buskers, and everything in between. When discussing Helen’s trial, the BBC said that “this was considered a relatively petty charge and usually resulted in a fine if proven wrong.” However, when Helen was brought to trial at the Old Bailey in London it was for charges under the archaic Witchcraft Act of 1735.

Britain’s ‘Last Witch Trial’

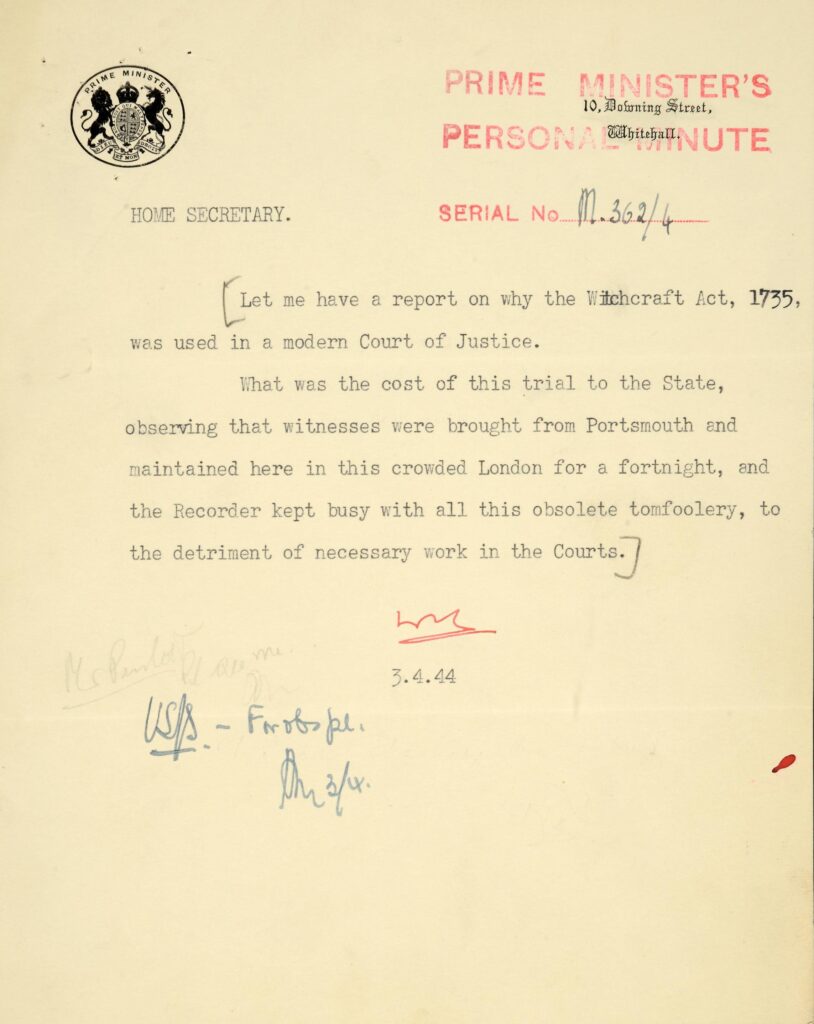

Helen’s trial is typically referred to as Britain’s ‘last witch trial’, but this is slightly misleading. While previous Witchcraft Acts condemned the act of witchcraft, the Witchcraft Act of 1735 made it a crime for an individual to claim they had magical powers or practiced witchcraft, which fit with the business Helen had been promoting for a number of decades. Naturally, a woman being charged under the Witchcraft Act of 1735 drew an outlandish amount of publicity. The idea of a witch trial happening in Britain in 1944 seemed both surprising and barbaric. Winston Churchill, Britain’s Prime Minister, found the entire spectacle appalling, addressing his frustration in a memo to the Home Secretary:

[Visit the Curious Archive article The History of the British Government’s UFO Files to see another interesting memo from Winston Churchill following an influx of UFO sightings in America]

Tomfoolery or not, the trial went on and witnesses came forward to confirm that Duncan was capable of the supernatural feats she claimed. Many witnesses were called to testify their experiences at Helen’s séances, including a journalist who claimed to see the ghost of Arthur Conan Doyle materialise. Photographs of Helen’s séances were shown as additional evidence, including photos of the medium’s ectoplasm. After what must have been a bizarre seven-day trial, the jury only took 25 minutes to find Helen guilty and she was sentenced to nine months in London’s Holloway Prison. Newspapers reported that Duncan collapsed when her sentence was announced.

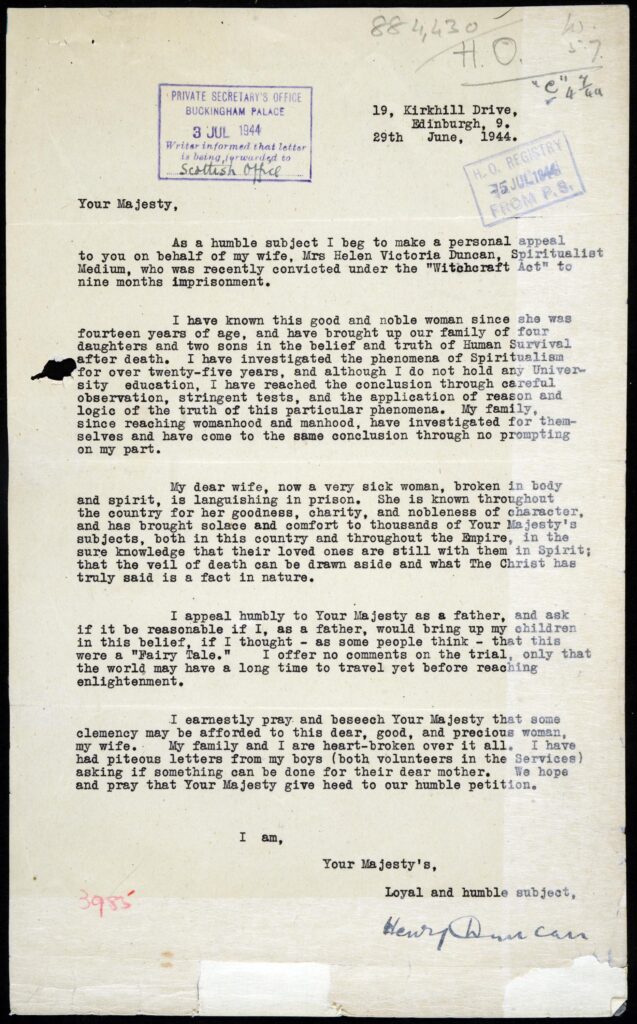

The trial and its outcome had an obvious effect on Helen and weighed terribly on her husband who wrote the following letter to the King begging him to make a personal appeal for his wife:

Whether or not Henry truly believed his wife could communicate with the dead, he certainly stuck by her side through the ups and downs of her unconventional career.

After serving six months of her sentence, Helen was released from prison on 22 September 1944. She continued to hold séances, with another raid occurring in 1955 in an unsuccessful attempt to prove fraud. On 6 December 1956, a few days after holding a séance, Helen died at her home in Edinburg at the age of 59. Despite reports from spiritualists that Helen’s death was ‘unusual’, she simply died from poor health that had affected her for a number of years.

While Helen wasn’t officially the ‘last witch’ to be convicted under The Witchcraft Act of 1735 (that ‘honour’ goes to Rebecca Yorke in 1944), she was the last to be imprisoned under it. In 1951, the act was repealed and replaced by the Fraudulent Mediums Act 1951 which “prohibited a person from claiming to be a psychic, medium, or other spiritualist while attempting to deceive and to make money from the deception (other than solely for the purpose of entertainment).” This act was also repealed in 2008 by the Consumer Protection from Unfair Trading Regulations 2008, a far cry from the first Witchcraft Act 1542 which considered witchcraft a crime punishable by death.

The Fight to Clear Helen’s Name

Helen’s story is almost exclusively one-sided and told primarily through the eyes of her sceptics. And since it happened to long ago, no one who witnessed her séances first-hand are alive to comment. However, six decades after her death, Helen’s grandchildren went on a mission to clear their grandmother’s name. In a BBC article from 2012 Graham Hewitt, who represented the grandchildren (and held the title of assistant General Secretary of the Spiritualists National Union), said that Helen was “tried under an old piece of legislation that shouldn’t have been used at the time and advice had been issued by the Director of Public Prosecutions that alternatives were available.” Hewitt also mentions Churchill’s own bewilderment that a witch trial was happening in the first place.

Supporters of Helen hoped she would be pardoned in a similar way as Alan Turing, the father of artificial intelligence, who received royal pardon from Queen Elizabeth II in 2013. However, Turning’s story is much different to Helen’s. In March of 1952, after crucial work cracking the Enigma code during WWII, Turing was convicted of “gross indecency” for being in a relationship with a man, which at the time was considered a crime. Since the law that found Turing guilty no longer exists (as with the Witchcraft Act 1735), Helen’s family hoped that a pardon would also be issued to their grandmother — though there is a clear difference in the severity of human rights violations between the two cases.

However, as of 2021 no pardon of Helen Duncan has been issued. Articles dried up after 2014 and it’s difficult to tell where the campaign currently stands. There was an official pardon website, but it no longer exists and can only be viewed through the Internet Archive Wayback Machine. The last updates on the website are from around 2008 when the Scottish government rejected the first petition to pardon the Helen. It then appears to have been abandoned.

Helen’s entire life is a peculiar but fascinating story. It’s clear that the physical spirits she produced were a hoax, but being tried under a 200 year old witchcraft law was particularly harsh. And if the Prime Minister himself thought the trial was complete nonsense, it probably was. It’s difficult to comment on the ethical side of what Helen was doing without having more unbiased documentation to analyse, but it’s clear that she was well loved within the spiritualist community (to Harry Price’s horror) and in high demand with the public. If a family needed a medium during the war to seek peace-of-mind, was Helen really committing any sort of ethical crime by helping them? But on the other hand, could charging money to perform parlour tricks for emotionally vulnerable people in itself be considered unethical? It’s an interesting conversation to have about mediums in general, but since Helen operated during a World War it raises a few other layers of ethical dilemmas. It will be interesting to see if Helen’s family resume their fight for her pardon, or if the Helen Duncan chapter of twentieth-century British spiritualism will remain closed.

[To read another investigation by Harry Price, visit the Curious Archive article The Ghost of Rosalie, an Investigation by Harry Price]

Sources and Additional Reading

BBC – Britain’s ‘last witch’: Campaign to pardon Helen Duncan

BBC – Scotland’s Last Witch

Clan Duncan Society – The Helen Duncan Story

HarryPriceWebsite.co.uk – The Cheese-Cloth Worshippers by Harry Price

History Answers – Victoria Helen Duncan and Britain’s World War II Witch Trial

History UK – Helen Duncan, Scotland’s Last Witch

How Stuff Works – What is Ectoplasm?

JSTOR Daily – Ectoplasm and the Last British Woman Tried for Witchcraft

The Guardian – Victorian ectoplasm-producing mediums: freaks or fakes?

University of Leeds – Possessing Her Audience: The Séances of Helen Duncan and the Power of the Female Medium

Wikipedia – Helen Duncan

Wikipedia – Witchcraft Act 1735